CHAPTER XVI. DINNER IN THE HALL OF BLOOMSBURY MARKET

As I spoke, I heard footsteps near the door; the latch yielded, and in came our two lovers, looking so handsome that one had no feeling of shame in looking on at their little-concealed love-making; for indeed it seemed as if all the world must be in love with them. As for old Hammond, he looked on them like an artist who has just painted a picture nearly as well as he thought he could when he began it, and was perfectly happy. He said:

“Sit down, sit down, young folk, and don’t make a noise. Our guest here has still some questions to ask me.”

“Well, I should suppose so,” said Dick; “you have only been three hours and a half together; and it isn’t to be hoped that the history of two centuries could be told in three hours and a half: let alone that, for all I know, you may have been wandering into the realms of geography and craftsmanship.”

“As to noise, my dear kinsman,” said Clara, “you will very soon be disturbed by the noise of the dinner-bell, which I should think will be very pleasant music to our guest, who breakfasted early, it seems, and probably had a tiring day yesterday.”

I said: “Well, since you have spoken the word, I begin to feel that it is so; but I have been feeding myself with wonder this long time past: really, it’s quite true,” quoth I, as I saw her smile, O so prettily! But just then from some tower high up in the air came the sound of silvery chimes playing a sweet clear tune, that sounded to my unaccustomed ears like the song of the first blackbird in the spring, and called a rush of memories to my mind, some of bad times, some of good, but all sweetened now into mere pleasure.

“No more questions now before dinner,” said Clara; and she took my hand as an affectionate child would, and led me out of the room and down stairs into the forecourt of the Museum, leaving the two Hammonds to follow as they pleased.

Queen's Dining Hall completed in 1866 - 1867

may resemble dining hall described by Guest.

We went into the market-place which I had been in before, a thinnish stream of elegantly dressed people going in along with us.

We turned into the cloister and came to a richly moulded and carved doorway, where a very pretty dark-haired young girl gave us each a beautiful bunch of summer flowers, and we entered a hall much bigger than that of the Hammersmith Guest House, more elaborate in its architecture and perhaps more beautiful. I found it difficult to keep my eyes off the wall-pictures (for I thought it bad manners to stare at Clara all the time, though she was quite worth it). I saw at a glance that their subjects were taken from queer old-world myths and imaginations which in yesterday’s world only about half a dozen people in the country knew anything about; and when the two Hammonds sat down opposite to us, I said to the old man, pointing to the frieze:

“How strange to see such subjects here!”

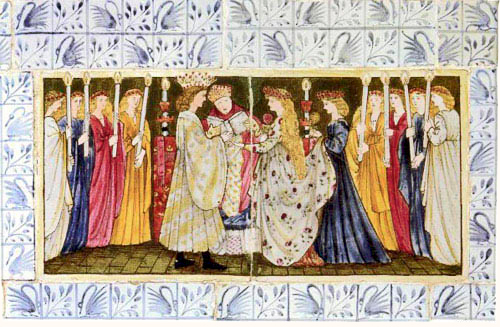

"Sleeping Beauty" with "Swan" border tiles designed by Edward Burne-Jones and

William Morris in 1862 - 1865, possibly painted by Lucy Faulkner 1864 - 1865

“Why?” said he. “I don’t see why you should be surprised; everybody knows the tales; and they are graceful and pleasant subjects, not too tragic for a place where people mostly eat and drink and amuse themselves, and yet full of incident.”

I smiled, and said: “Well, I scarcely expected to find record of the Seven Swans and the King of the Golden Mountain and Faithful Henry, and such curious pleasant imaginations as Jacob Grimm got together from the childhood of the world, barely lingering even in his time: I should have thought you would have forgotten such childishness by this time.”

The old man smiled, and said nothing; but Dick turned rather red, and broke out:

“What DO you mean, guest? I think them very beautiful, I mean not only the pictures, but the stories; and when we were children we used to imagine them going on in every wood-end, by the bight of every stream: every house in the fields was the Fairyland King’s House to us. Don’t you remember, Clara?”

“Yes,” she said; and it seemed to me as if a slight cloud came over her fair face. I was going to speak to her on the subject, when the pretty waitresses came to us smiling, and chattering sweetly like reed warblers by the river side, and fell to giving us our dinner. As to this, as at our breakfast, everything was cooked and served with a daintiness which showed that those who had prepared it were interested in it; but there was no excess either of quantity or of gourmandise; everything was simple, though so excellent of its kind; and it was made clear to us that this was no feast, only an ordinary meal. The glass, crockery, and plate were very beautiful to my eyes, used to the study of mediaeval art; but a nineteenth-century club-haunter would, I daresay, have found them rough and lacking in finish; the crockery being lead-glazed pot-ware, though beautifully ornamented; the only porcelain being here and there a piece of old oriental ware.

“Yes,” she said; and it seemed to me as if a slight cloud came over her fair face. I was going to speak to her on the subject, when the pretty waitresses came to us smiling, and chattering sweetly like reed warblers by the river side, and fell to giving us our dinner. As to this, as at our breakfast, everything was cooked and served with a daintiness which showed that those who had prepared it were interested in it; but there was no excess either of quantity or of gourmandise; everything was simple, though so excellent of its kind; and it was made clear to us that this was no feast, only an ordinary meal. The glass, crockery, and plate were very beautiful to my eyes, used to the study of mediaeval art; but a nineteenth-century club-haunter would, I daresay, have found them rough and lacking in finish; the crockery being lead-glazed pot-ware, though beautifully ornamented; the only porcelain being here and there a piece of old oriental ware.

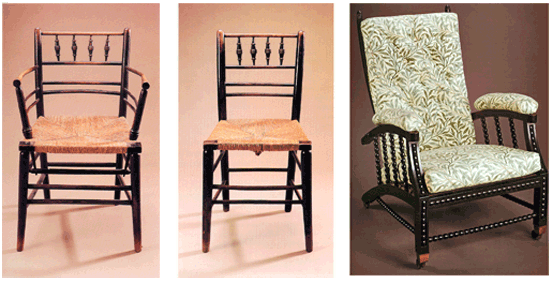

The glass, again, though elegant and quaint, and very varied in form, was somewhat bubbled and hornier in texture than the commercial articles of the nineteenth century. The furniture and general fittings of the ball were much of a piece with the table-gear, beautiful in form and highly ornamented, but without the commercial “finish” of the joiners and cabinet-makers of our time. Withal, there was a total absence of what the nineteenth century calls “comfort”—that is, stuffy inconvenience; so that, even apart from the delightful excitement of the day, I had never eaten my dinner so pleasantly before.

Sussex Chair 1865, and the Morris Reclinable back chair 1866 made by the Morris Company.

When we had done eating, and were sitting a little while, with a bottle of very good Bordeaux wine before us, Clara came back to the question of the subject-matter of the pictures, as though it had troubled her.

She looked up at them, and said: “How is it that though we are so interested with our life for the most part, yet when people take to writing poems or painting pictures they seldom deal with our modern life, or if they do, take good care to make their poems or pictures unlike that life? Are we not good enough to paint ourselves? How is it that we find the dreadful times of the past so interesting to us— in pictures and poetry?”

Old Hammond smiled. “It always was so, and I suppose always will be,” said he, “however it may be explained. It is true that in the nineteenth century, when there was so little art and so much talk about it, there was a theory that art and imaginative literature ought to deal with contemporary life; but they never did so; for, if there was any pretence of it, the author always took care (as Clara hinted just now) to disguise, or exaggerate, or idealise, and in some way or another make it strange; so that, for all the verisimilitude there was, he might just as well have dealt with the times of the Pharaohs.”

“Well,” said Dick, “surely it is but natural to like these things strange; just as when we were children, as I said just now, we used to pretend to be so-and-so in such-and-such a place. That’s what these pictures and poems do; and why shouldn’t they?”

“Thou hast hit it, Dick,” quoth old Hammond; “it is the child-like part of us that produces works of imagination. When we are children time passes so slow with us that we seem to have time for everything.”

He sighed, and then smiled and said: “At least let us rejoice that we have got back our childhood again. I drink to the days that are!”

“Second childhood,” said I in a low voice, and then blushed at my double rudeness, and hoped that he hadn’t heard. But he had, and turned to me smiling, and said: “Yes, why not? And for my part, I hope it may last long; and that the world’s next period of wise and unhappy manhood, if that should happen, will speedily lead us to a third childhood: if indeed this age be not our third. Meantime, my friend, you must know that we are too happy, both individually and collectively, to trouble ourselves about what is to come hereafter.”

“Well, for my part,” said Clara, “I wish we were interesting enough to be written or painted about.”

Dick answered her with some lover’s speech, impossible to be written down, and then we sat quiet a little.