CHAPTER VII. TRAFALGAR SQUARE

CHAPTER VII. TRAFALGAR SQUARE

And now again I was busy looking about me, for we were quite clear of Piccadilly Market, and were in a region of elegantly-built much ornamented houses, which I should have called villas if they had been ugly and pretentious, which was very far from being the case. Each house stood in a garden carefully cultivated, and running over with flowers. The blackbirds were singing their best amidst the garden-trees, which, except for a bay here and there, and occasional groups of limes, seemed to be all fruit-trees: there were a great many cherry-trees, now all laden with fruit; and several times as we passed by a garden we were offered baskets of fine fruit by children and young girls. Amidst all these gardens and houses it was of course impossible to trace the sites of the old streets: but it seemed to me that the main roadways were the same as of old.

We came presently into a large open space, sloping somewhat toward the south, the sunny site of which had been taken advantage of for planting an orchard, mainly, as I could see, of apricot-trees, in the midst of which was a pretty gay little structure of wood, painted and gilded, that looked like a refreshment-stall. From the southern side of the said orchard ran a long road, chequered over with the shadow of tall old pear trees, at the end of which showed the high tower of the Parliament House, or Dung Market.

A strange sensation came over me; I shut my eyes to keep out the sight of the sun glittering on this fair abode of gardens, and for a moment there passed before them a phantasmagoria of another day. A great space surrounded by tall ugly houses, with an ugly church at the corner and a nondescript ugly cupolaed building at my back; the roadway thronged with a sweltering and excited crowd, dominated by omnibuses crowded with spectators. In the midst a paved be-fountained square, populated only by a few men dressed in blue, and a good many singularly ugly bronze images (one on the top of a tall column). The said square guarded up to the edge of the roadway by a four-fold line of big men clad in blue, and across the southern roadway the helmets of a band of horse-soldiers, dead white in the greyness of the chilly November afternoon—I opened my eyes to the sunlight again and looked round me, and cried out among the whispering trees and odorous blossoms, “Trafalgar Square!”

“Yes,” said Dick, who had drawn rein again, “so it is. I don’t wonder at your finding the name ridiculous: but after all, it was nobody’s business to alter it, since the name of a dead folly doesn’t bite. Yet sometimes I think we might have given it a name which would have commemorated the great battle which was fought on the spot itself in 1952,—that was important enough, if the historians don’t lie.”

“Which they generally do, or at least did,” said the old man. “For instance, what can you make of this, neighbours? I have read a muddled account in a book—O a stupid book—called James’ Social Democratic History, of a fight which took place here in or about the year 1887 (I am bad at dates). Some people, says this story, were going to hold a ward-mote here, or some such thing, and the Government of London, or the Council, or the Commission, or what not other barbarous half-hatched body of fools, fell upon these citizens (as they were then called) with the armed hand. That seems too ridiculous to be true; but according to this version of the story, nothing much came of it, which certainly IS too ridiculous to be true.”

“Well,” quoth I, “but after all your Mr. James is right so far, and it IS true; except that there was no fighting, merely unarmed and peaceable people attacked by ruffians armed with bludgeons.”

“And they put up with that?” said Dick, with the first unpleasant expression I had seen on his good-tempered face.

Said I, reddening: “We HAD to put up with it; we couldn’t help it.”

The old man looked at me keenly, and said: “You seem to know a great deal about it, neighbour! And is it really true that nothing came of it?”

“This came of it,” said I, “that a good many people were sent to prison because of it.”

“What, of the bludgeoners?” said the old man. “Poor devils!”

“No, no,” said I, “of the bludgeoned.”

Said the old man rather severely: “Friend, I expect that you have been reading some rotten collection of lies, and have been taken in by it too easily.”

“I assure you,” said I, “what I have been saying is true.”

“Well, well, I am sure you think so, neighbour,” said the old man, “but I don’t see why you should be so cocksure.”

As I couldn’t explain why, I held my tongue. Meanwhile Dick, who had been sitting with knit brows, cogitating, spoke at last, and said gently and rather sadly:

“How strange to think that there have been men like ourselves, and living in this beautiful and happy country, who I suppose had feelings and affections like ourselves, who could yet do such dreadful things.”

“Yes,” said I, in a didactic tone; “yet after all, even those days were a great improvement on the days that had gone before them. Have you not read of the Mediaeval period, and the ferocity of its criminal laws; and how in those days men fairly seemed to have enjoyed tormenting their fellow men?—nay, for the matter of that, they made their God a tormentor and a jailer rather than anything else.”

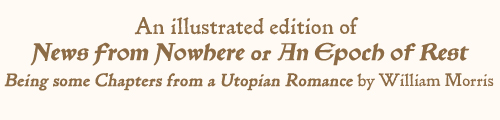

“Yes,” said Dick, “there are good books on that period also, some of which I have read. But as to the great improvement of the nineteenth century, I don’t see it. After all, the Mediaeval folk acted after their conscience, as your remark about their God (which is true) shows, and they were ready to bear what they inflicted on others; whereas the nineteenth century ones were hypocrites, and pretended to be humane, and yet went on tormenting those whom they dared to treat so by shutting them up in prison, for no reason at all, except that they were what they themselves, the prison-masters, had forced them to be. O, it’s horrible to think of!”

“But perhaps,” said I, “they did not know what the prisons were like.”

Exterior of Newgate Prison, 1896 — Cell in Newgate Prison and a view of the hall leading to the cells, 1896

The cells in Newgate were switched to a single cell system in 1858.

Dick seemed roused, and even angry. “More shame for them,” said he, “when you and I know it all these years afterwards. Look you, neighbour, they couldn’t fail to know what a disgrace a prison is to the Commonwealth at the best, and that their prisons were a good step on towards being at the worst.”

Quoth I: “But have you no prisons at all now?”

As soon as the words were out of my mouth, I felt that I had made a mistake, for Dick flushed red and frowned, and the old man looked surprised and pained; and presently Dick said angrily, yet as if restraining himself somewhat —

“Man alive! how can you ask such a question? Have I not told you that we know what a prison means by the undoubted evidence of really trustworthy books, helped out by our own imaginations? And haven’t you specially called me to notice that the people about the roads and streets look happy? and how could they look happy if they knew that their neighbours were shut up in prison, while they bore such things quietly? And if there were people in prison, you couldn’t hide it from folk, like you may an occasional man-slaying; because that isn’t done of set purpose, with a lot of people backing up the slayer in cold blood, as this prison business is. Prisons, indeed! O no, no, no!”

He stopped, and began to cool down, and said in a kind voice: “But forgive me! I needn’t be so hot about it, since there are NOT any prisons: I’m afraid you will think the worse of me for losing my temper. Of course, you, coming from the outlands, cannot be expected to know about these things. And now I’m afraid I have made you feel uncomfortable.”

In a way he had; but he was so generous in his heat, that I liked him the better for it, and I said:

“No, really ’tis all my fault for being so stupid. Let me change the subject, and ask you what the stately building is on our left just showing at the end of that grove of plane-trees?”

National Gallery, 1896

I didn’t try to enlighten him, feeling the task too heavy; but I pulled out my magnificent pipe and fell a-smoking, and the old horse jogged on again. As we went, I said:

“This pipe is a very elaborate toy, and you seem so reasonable in this country, and your architecture is so good, that I rather wonder at your turning out such trivialities.”

It struck me as I spoke that this was rather ungrateful of me, after having received such a fine present; but Dick didn’t seem to notice my bad manners, but said:

“Well, I don’t know; it is a pretty thing, and since nobody need make such things unless they like, I don’t see why they shouldn’t make them, if they like. Of course, if carvers were scarce they would all be busy on the architecture, as you call it, and then these ‘toys’ (a good word) would not be made; but since there are plenty of people who can carve—in fact, almost everybody, and as work is somewhat scarce, or we are afraid it may be, folk do not discourage this kind of petty work.”

He mused a little, and seemed somewhat perturbed; but presently his face cleared, and he said: “After all, you must admit that the pipe is a very pretty thing, with the little people under the trees all cut so clean and sweet;—too elaborate for a pipe, perhaps, but—well, it is very pretty.”

“Too valuable for its use, perhaps,” said I.

“What’s that?” said he; “I don’t understand.”

I was just going in a helpless way to try to make him understand, when we came by the gates of a big rambling building, in which work of some sort seemed going on. “What building is that?” said I, eagerly; for it was a pleasure amidst all these strange things to see something a little like what I was used to: “it seems to be a factory.”

“Yes,” he said, “I think I know what you mean, and that’s what it is; but we don’t call them factories now, but Banded-workshops: that is, places where people collect who want to work together.”

“I suppose,” said I, “power of some sort is used there?”

Burleigh pottery factory

“No, no,” said he. “Why should people collect together to use power, when they can have it at the places where they live, or hard by, any two or three of them; or any one, for the matter of that? No; folk collect in these Banded-workshops to do hand-work in which working together is necessary or convenient; such work is often very pleasant. In there, for instance, they make pottery and glass,—there, you can see the tops of the furnaces. Well, of course it’s handy to have fair-sized ovens and kilns and glass-pots, and a good lot of things to use them for: though of course there are a good many such places, as it would be ridiculous if a man had a liking for pot-making or glass-blowing that he should have to live in one place or be obliged to forego the work he liked.”

“I see no smoke coming from the furnaces,” said I.

“Smoke?” said Dick; “why should you see smoke?”

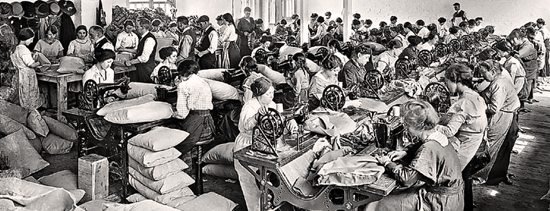

Glass blower & mold boy, 1908

I held my tongue, and he went on: “It’s a nice place inside, though as plain as you see outside. As to the crafts, throwing the clay must be jolly work: the glass-blowing is rather a sweltering job; but some folk like it very much indeed; and I don’t much wonder: there is such a sense of power, when you have got deft in it, in dealing with the hot metal. It makes a lot of pleasant work,” said he, smiling, “for however much care you take of such goods, break they will, one day or another, so there is always plenty to do.”

I held my tongue and pondered.

We came just here on a gang of men road-mending which delayed us a little; but I was not sorry for it; for all I had seen hitherto seemed a mere part of a summer holiday; and I wanted to see how this folk would set to on a piece of real necessary work. They had been resting, and had only just begun work again as we came up; so that the rattle of the picks was what woke me from my musing. There were about a dozen of them, strong young men, looking much like a boating party at Oxford would have looked in the days I remembered, and not more troubled with their work: their outer raiment lay on the road-side in an orderly pile under the guardianship of a six-year-old boy, who had his arm thrown over the neck of a big mastiff, who was as happily lazy as if the summer-day had been made for him alone. As I eyed the pile of clothes, I could see the gleam of gold and silk embroidery on it, and judged that some of these workmen had tastes akin to those of the Golden Dustman of Hammersmith. Beside them lay a good big basket that had hints about it of cold pie and wine: a half dozen of young women stood by watching the work or the workers, both of which were worth watching, for the latter smote great strokes and were very deft in their labour, and as handsome clean-built fellows as you might find a dozen of in a summer day. They were laughing and talking merrily with each other and the women, but presently their foreman looked up and saw our way stopped. So he stayed his pick and sang out, “Spell ho, mates! here are neighbours want to get past.” Whereon the others stopped also, and, drawing around us, helped the old horse by easing our wheels over the half undone road, and then, like men with a pleasant task on hand, hurried back to their work, only stopping to give us a smiling good-day; so that the sound of the picks broke out again before Greylocks had taken to his jog-trot. Dick looked back over his shoulder at them and said:

“They are in luck to-day: it’s right down good sport trying how much pick-work one can get into an hour; and I can see those neighbours know their business well. It is not a mere matter of strength getting on quickly with such work; is it, guest?”

“I should think not,” said I, “but to tell you the truth, I have never tried my hand at it.”

“Really?” said he gravely, “that seems a pity; it is good work for hardening the muscles, and I like it; though I admit it is pleasanter the second week than the first. Not that I am a good hand at it: the fellows used to chaff me at one job where I was working, I remember, and sing out to me, ‘Well rowed, stroke!’ ‘Put your back into it, bow!’”

“Not much of a joke,” quoth I.

“Well,” said Dick, “everything seems like a joke when we have a pleasant spell of work on, and good fellows merry about us; we feel so happy, you know.” Again I pondered silently.